To clear the throat in memoir or not: That is the question. Whether it is nobler to the reader’s mind to have the narrator suffer the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune in a book’s first pages or to wait to have the reader take arms against a sea of troubles in the rest of the story, and by waiting, lose the reader entirely?

I’ll drop the Shakespeare for just a moment because this is serious business. We need to talk about whether memoirs need prologues.

You might be in the same position I was a couple of weeks ago. I was working on my new project, an 80s memoir about houses, and I had finished a first chapter. It was pretty good. What to do: Go on to the next chapter, chapter 2? Wait, do I need a prologue for this thing? Is this really the beginning? Does it feel like a slow burn or is it gripping enough that it will hold a reader’s interest at the most important part of the book?

The quick answer to whether or not you need a prologue in memoir is: It’s complicated.

Time is of the essence. Pacing is important. The world, and the reader, waits for no one. You can’t save your best writing for later in the book when the next person to pick it up has only downloaded that free sample from Amazon.

And so, some writers, having reflected on whether or not they need a prologue, throw one in there when they realize their first chapters are not exciting enough. They take their most exciting scene, the one that leaves the reader enraptured, wondering what could possibly happen next – how in the world did this person get in this situation in the first place!!?? – and they take on a prologue to raise the stakes earlier on.

“Just ask the agent!” some advisors say.

“Your editor will decide!” others type out in message boards.

True, true, but if I am going to make this art, I need to have an opinion, at the very least as it reflects my own work and process.

In a way a prologue in memoir is not that different than a prologue in a novel. So I took a couple of my favorite memoirs and looked at the beginnings of things.

Here is the work a prologue can do in memoir:

- It can set the tone for the rest of the book.

Memoir can only really happen when time passes and the self reflects back differently on what occurred. For many readers, this is the draw of memoir entirely: The reflective self piecing together meaning from life’s sometimes random events. Prologues can establish that reflective voice, in a desired and appropriate tone, at the beginning, before the book’s major events kick off. - It can set a framework.

As Beth Kephart has said, memoir is structure – it is how the writer makes meaning. In some memoir, the structure informs the narrative, and in others, the structure is the narrative. Think about books like Eat. Pray. Love., where Elizabeth Gilbert explains why she chose to structure her book in 108 short chapters (the number of prayer beads on the japa mala). - It can create drama.

Here, Wild: From Lost to Found on the Pacific Crest Trailis the best example (and perhaps best-known among memoir lovers right now). Strayed begins her book with a moment when she loses one of her boots down a cliff side and decides, in her grief and anguish, to throw the other one after it. It’s the opposite of a Dorothy’s ruby shoes moment. We see right away the depth of her sorrow and are thrust into the thick of danger: A woman alone, hiking the PCT.

The Sound of a Wild Snail Eating by Elizabeth Tova Bailey

by Elizabeth Tova Bailey

Story: This slim volume recounts the author’s survival of a year’s-long mystery illness as she watches the toils of a snail from her hospital bed. Lots of snail story here.

Prologue: Yes.

Tone: Reflective, detached, bare bones, drama enough without added drama, inquisitive

What comes next: The author’s friend finds a snail while walking and brings it to her bedside at the hospital. The chapter recounts the author’s falling ill in greater detail than in the prologue and uses the snail in a pot of violets as a contrast to the hospital space, nature and science, life and sickness. It’s a slow mover, for sure, but there is a wonderful poetry to the writing.

Reasoning: This is one of those prologues that falls squarely into the category of “Something terrible is wrong with me and I have no idea what it is.” It’s a scene of the author discovering she can’t move, and it’s terrifying in its simplicity. She falls ill. She is deeply afraid. It ends with the line: “I try to watch over myself; if I go to sleep, I might never wake up again. My suspicion is that the prologue was necessary here to heighten the drama and the uncertainty before introducing the much slower page of the next chapters, in which the reader, along with the narrator, grapples literally and figuratively with this new slowness in life.

Does it work: Absolutely, in part because the language doesn’t feel manipulative – forced into the dramatic just to grab the reader. You could say she totally snailed it.

Buy The Sound of a Wild Snail Eating.

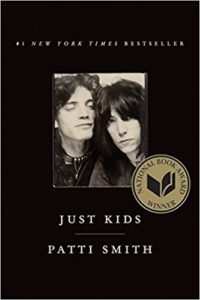

Just Kids by Patti Smith

by Patti Smith

Story: Rocker poet goddess Patti Smith tells the story of her two-decade friendship with artist Robert Mapplethrope, beginning when they were starving artists in the late 1960s New York City arts scene.

Prologue: Yes, though she calls a “Forward.”

Tone: Reminiscent, somewhat regretful, an adult looking back on youth

What comes next: Smith enters the story in of a misfit childhood growing up with artistic inclinations, very much a portrait of the artist as a young woman as a story of an artistic friendship.

Reasoning: The framing of this book is the friendship between the two artists, but Smith smartly begins by tracing her evolution before meeting Maplethorpe. The forward recounts the scene where Smith learns of Mapplethorpe’s death, years after their romantic relationship had ended, when their artistic collaborations had all but subsided. She is experiencing his death as something profoundly terrifying, a jolt to her system that kick-starts the look back on his part in her life, and hers in his. This is a standard approach in memoir, by the way, to introduce the “remembering self” before the self gets remembered. It is a way to begin not at the very beginning, but to let the reader know that there is going to be a disconnect between the voice on the page and the events as they occur – that the events are filtered through a remembered self as opposed to a self who hasn’t given any thought or interpretation to the events.

Does it work: It’s an interesting approach – so relatable! It’s a passage of adulthood: To learn of the death of a dear friend whose life touched yours and to demand space, and time, to reflect on it. It’s a nice start to a book about two profoundly intertwined artists.

The Authenticity Experiment by Kate Carroll De Gutes

by Kate Carroll De Gutes

Story: An award-winning essayist decides to be 100% authentic on social media to discover what happens when you stop curating your online presence.

Prologue: Yes.

Tone: Explanatory, vulnerable

What comes next: A short essay laying out that the author is interested in both the dark and light of life, in figuring out why humans react on social media instead of pushing towards change, especially the change that can happen from within.

Reasoning: De Gutes’s book emerged from an experiment, so her prologue serves to outline the framework of that experiment: How long, why, how much. It is the origin story for a project on that much maligned term authenticity, but it is also a call-to-action, or at least, to understanding, that the new “back fence” of social media still has its own hilarious boundaries.

Does it work: How brilliant of her – to anticipate questions readers, editors, and reviewers might have about the project and pull them out into a prologue, thus saving the real raw humanity for the book? It’s a nuts and bolts section, but it has just enough of De Gutes’s adorable vulnerability to not get bogged down in the protocols. I’m not always a fan of “My Year Of” memoirs, but this one seems far less gimmicky that most.

Buy The Authenticity Experiment.

Did I decide to prologue?

In a word, no. I did write one, but the voice was completely different than what I had established in my first chapter (the one I had really liked). It felt like an essay unto itself, not a beginning, or even a chapter. It told too much of the story, it felt too “quiet” for me. In the end, I scrapped the whole thing entirely and am just beginning with chapter 1.

Sometimes that happens with writing — you have to clear the brush to find the path. But then, the glorious feeling of being on one!

Did you like this post? I write a monthly creativity newsletter featuring a lot of memoir writing content. You can sign up below.

Subscribe to the Wayfinder newsletter and a FREE download.

I have put together a FREE, downloadable PDF so we can start the conversation on creative wayfinding. It's called:

"10 Game-changing Takeaways for the Professional Creative Life"

Get it by subscribing to the Wayfinder.